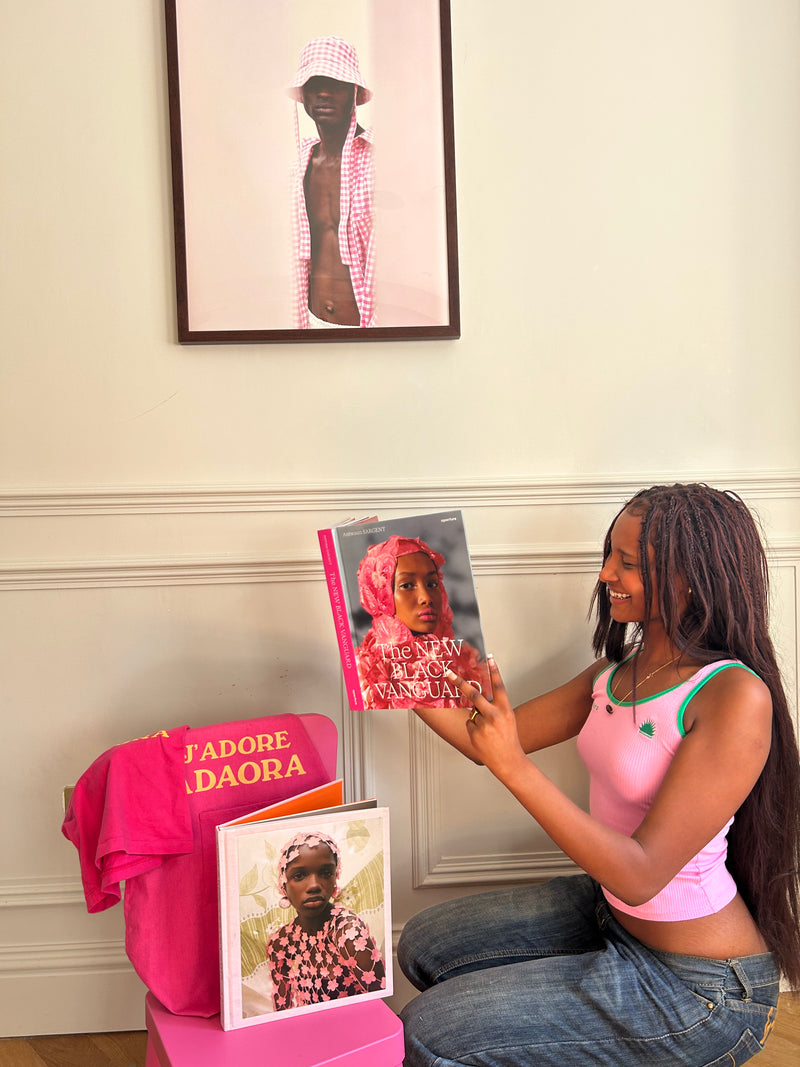

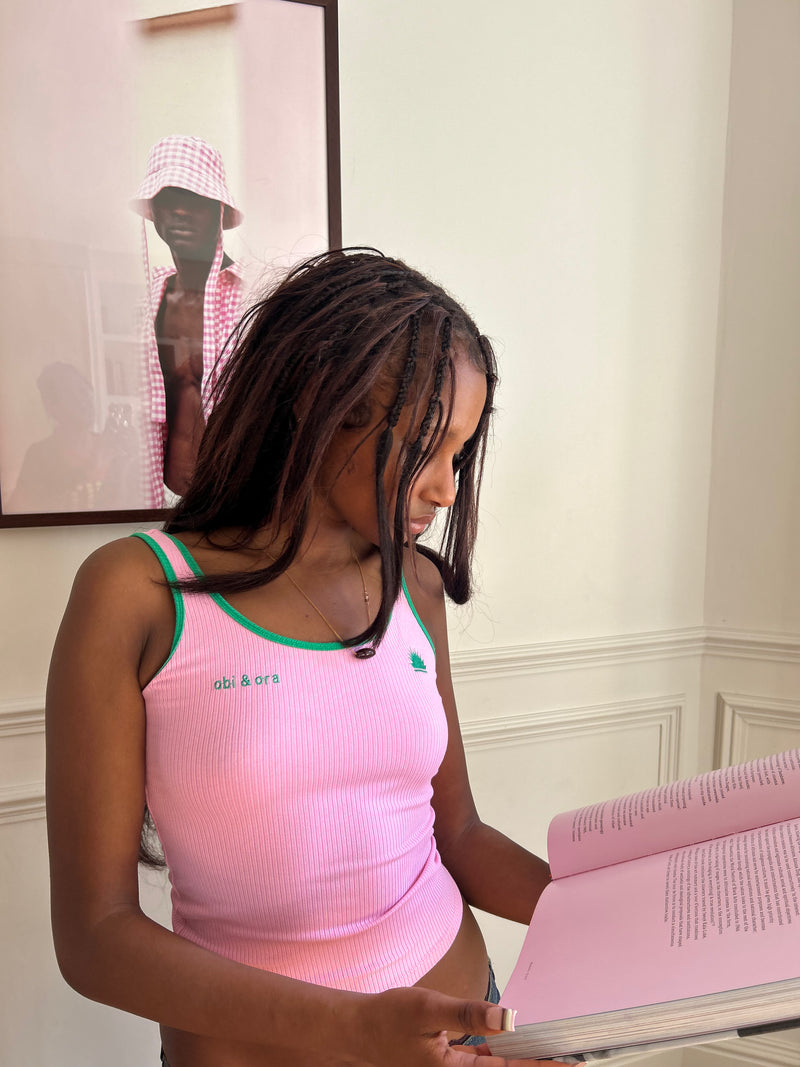

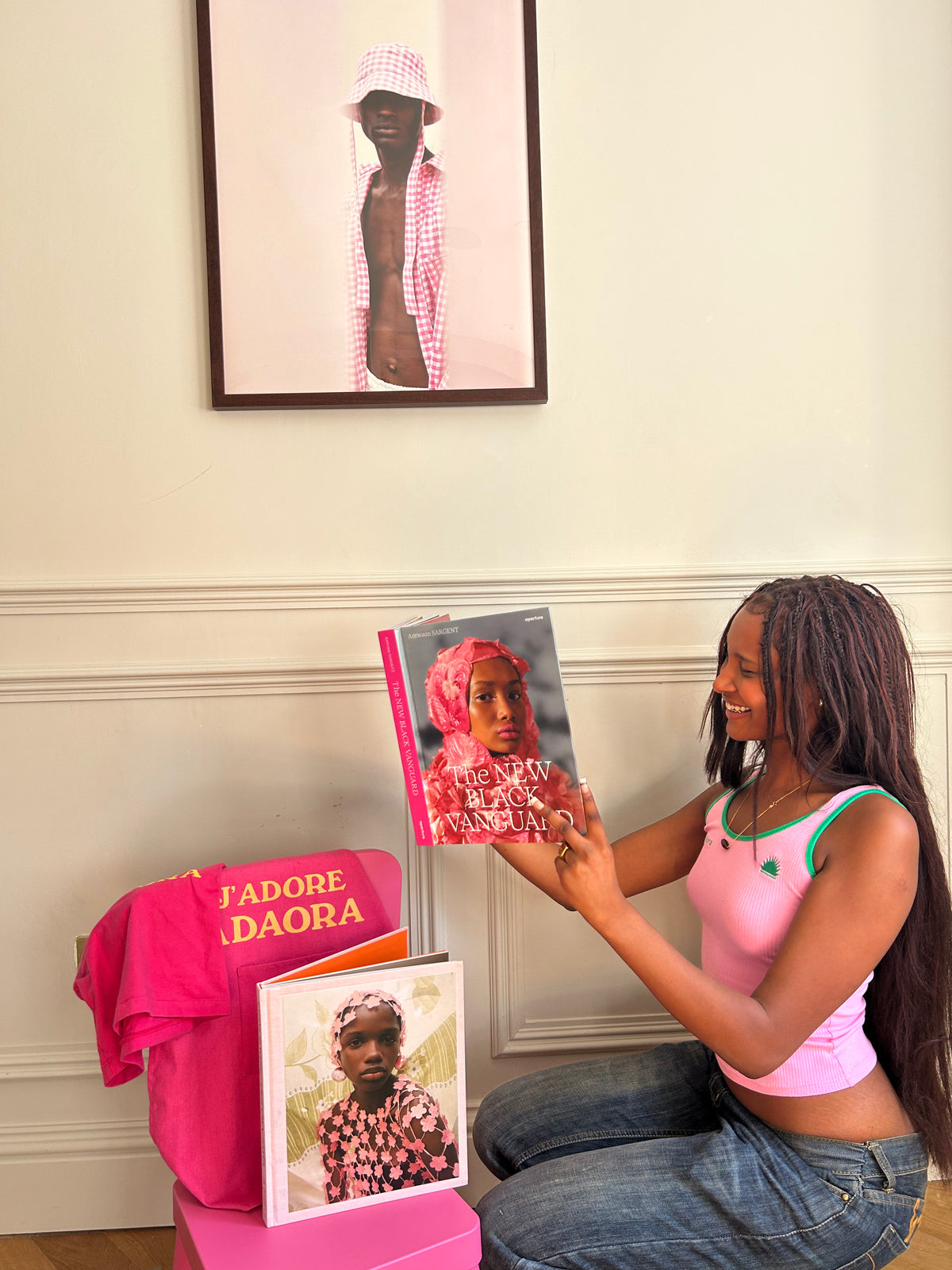

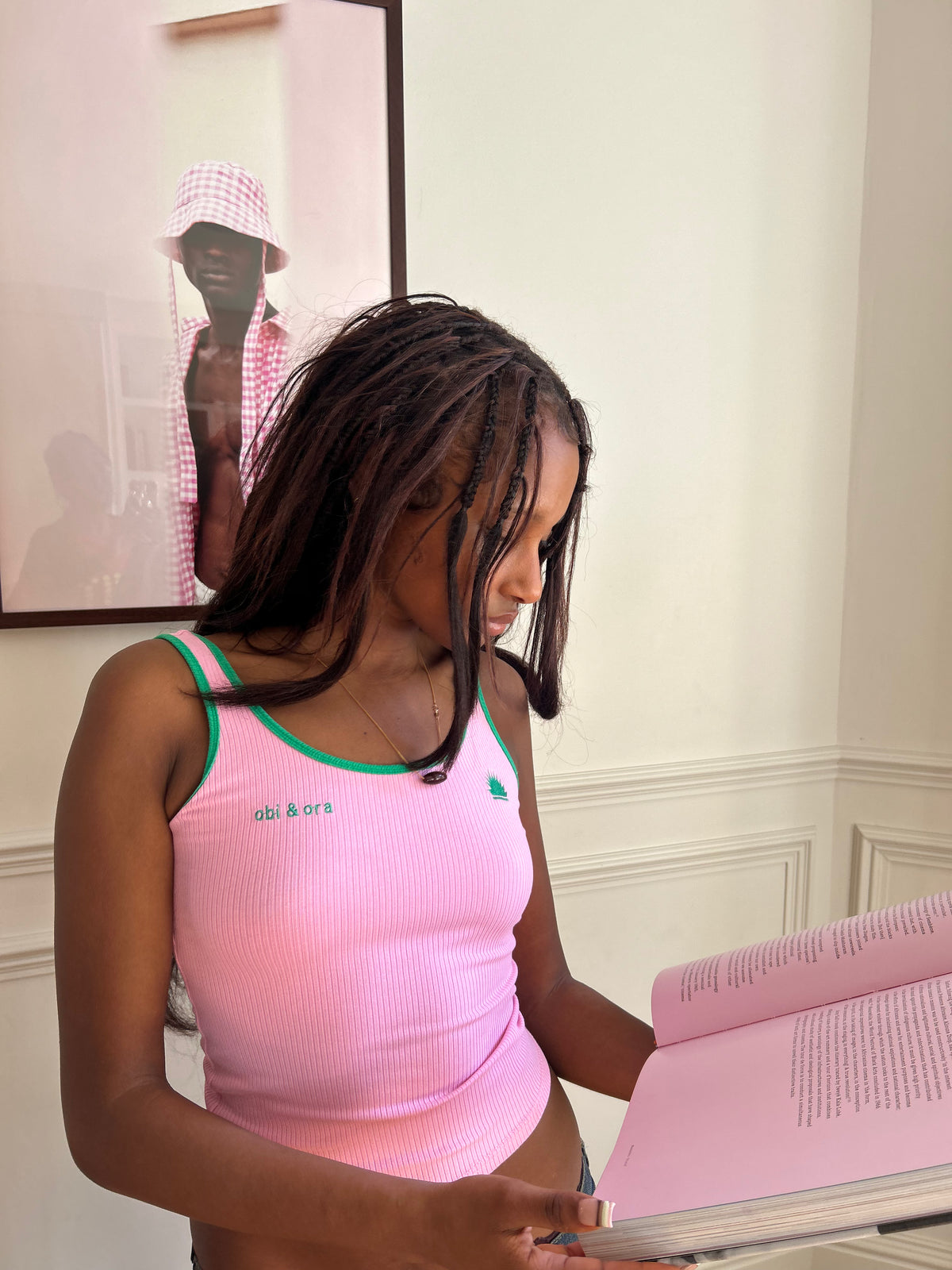

Óbí & Òra ribbed logo vest top

Killa Pink

Regular price

£65.00

Regular price

Sale price

£65.00

Unit price

per

Couldn't load pickup availability